What Happens to Our Mind When We Become Heightened?

Stress; we all know what it is and what it feels like, we all know that excessive stress can be detrimental to our long-term mental and physical health. What is somewhat less understood is what is actually happening in our brain when we become stressed, and what impact this has on our ability to think and perform.

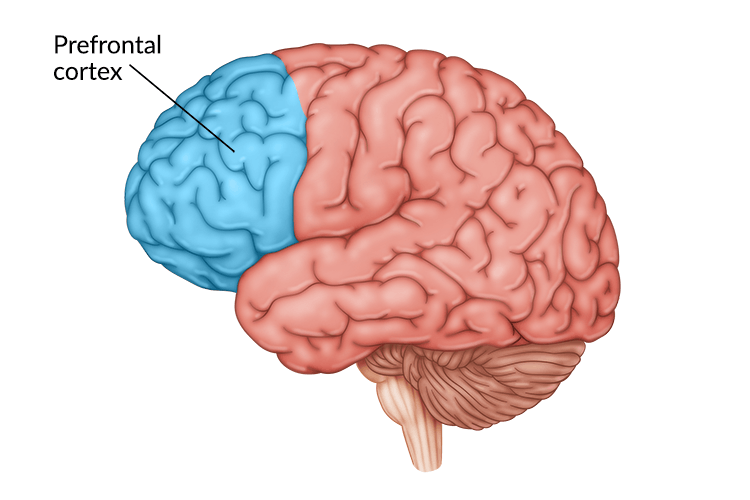

The Pre-frontal Cortex

One of the primary areas that is impacted by stress is the pre-frontal cortex:

The pre-frontal cortex is primarily responsible for our higher order cognitive functions; problem solving, decision making, planning, etc. (Arnsten 2009).

This is the part of the brain that we use for our conscious, intentional thinking. To use a metaphor; if the lower parts of the brain and the body were to be considered a horse, the pre-frontal cortex would be the horse-rider. The horse is capable of walking, eating, breathing and all of the basic biological functions independent of of the rider, the horse may even be able to find its way from one place to another reliably, if they have travelled the path many times. However, for the horse to race, work or travel to new locations, a horse-rider must be present to guide the horse. This is how the brain operates; biological functions, basic or repetitive tasks, well-practiced activities and instinctual functions do not require the input of the pre-frontal cortex.

What happens to the pre-frontal cortex when we become stressed?

Our stress response begins in our brain when we are confronted with, or perceive there to be, impending danger. The eyes, ears or both send information to the amygdala, a part of the brain that contributes to emotional processing, the amygdala then sends a signal to the hypothalamus to activate our fight or flight response.

What does this mean for the pre-frontal cortex?

Once our brain activates our fight or flight response our ability to engage our pre-frontal cortex drops to nearly zero. If you imagine a time when you were at your maximum level of panic, it likely felt as if you were taking action or reacting without thinking; in fact, your brain was still operating and sending messages. The feeling of acting without thinking comes from the fact that the pre-frontal cortex is not engaged during a fight or flight response and you are therefore not consciously making decisions or problem solving.

So, what does this mean for stress and performance?

We have discussed what happens to the pre-frontal cortex when the fight or flight response is activated, this is a rarity. Where understanding the connection between stress and the function of our pre-frontal cortex really becomes useful is when we realise that the connection between stress and the function of our pre-frontal cortex is not all or nothing. A small increase in stress corresponds with a small decrease in our ability to engage our pre-frontal cortex, a large increase in stress corresponds with a large decrease in our ability to engage our pre-frontal cortex.

We can notice this impact throughout our day, particularly in a work setting. A disengaged pre-frontal cortex can feel like brain fog or difficulty making decisions, this reduced capacity can also lead to an avoidance of complex tasks. This can lead to a sense of being overwhelmed as the brain is less able to separate out and address our individual stressors and is more likely to view all stressors as an insurmountable mountain.

We can utilise this knowledge to maximise performance in any setting in which we may be impacted by stress. We must first put our effort into noticing when we are heightened, looking out for the symptoms and impacts of stress. Once it has been recognised that stress is heightened, the task becomes taking steps to manage this stress. This can be achieved with a wide range of mindfulness activities depending on context and preference. Some common strategies are:

- Breathing techniques

- Contacting the present moment

- Meditation

- Visualisation

- Self-acceptance/kindness

Becoming aware of your stress level, the impact this has on the engagement of our pre-frontal cortex, and strategies for reducing stress in the moment allows you to take control of and super-charge your cognitive abilities - give it a try, you may be surprised by the results!

References:

Arnsten AF. Stress Signaling Pathways that Impair Pre-frontal Cortex Structure and Function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Jun; 10(6):410-22. doi 10.1038/nrn2648. PMID: 19455173; PMCID: PMC2907136, and

'Prefrontal Cortex Damage: Understanding the Effects & Methods for Recovery', Written by Flint Rehab. Medically Reviewed by Elizabeth Denslow, OTR/L. Last Updated on July 7, 2023.